This week's blog comes from Ryan Kilpatrick, Executive Director of Housing Next.

This week's blog comes from Ryan Kilpatrick, Executive Director of Housing Next.

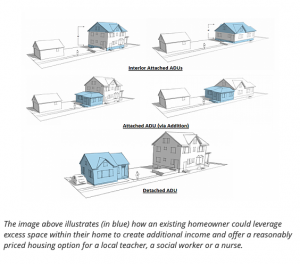

Long considered the unwanted neighborhood step-child, homes with an extra dwelling unit offer an extraordinary opportunity to make a significant difference in the availability of housing throughout West Michigan and to build wealth for young entrepreneurs through local investments. All we have to do is allow them to exist.

There has been a barrage of news in the last few years about the dire situation most growing communities face when it comes to housing supply. If your local economy has grown in the last 10 years, the chances are very good that your community has a shortage of housing units compared to the number of individuals and families who are looking for housing. As a basic rule of economics, when a resource is scarce, the price goes up. This is certainly true when it comes to housing. However, while there is a shortage of individual housing units (i.e. apartments, condos, town homes and even single family homes), there may not be a shortage of livable space in many communities. What's the difference?

There has been a barrage of news in the last few years about the dire situation most growing communities face when it comes to housing supply. If your local economy has grown in the last 10 years, the chances are very good that your community has a shortage of housing units compared to the number of individuals and families who are looking for housing. As a basic rule of economics, when a resource is scarce, the price goes up. This is certainly true when it comes to housing. However, while there is a shortage of individual housing units (i.e. apartments, condos, town homes and even single family homes), there may not be a shortage of livable space in many communities. What's the difference?

Let’s think about some possible scenarios.

In 2008 Mike and Nancy, a middle-class couple in their mid-fifties, were at the height of their earning potential when the stock market plunged, wiping out much of their retirement savings. At the same time, the value of their home fell by 30%. Thankfully, neither of them lost their job during the recession, but Nancy had her hours cut to part-time, while Mike didn’t see a pay increase for nearly six years. Simultaneously, both of their kids were enrolled in four-year degree programs and any extra cash was being used to try to limit the amount of debt their children took on to pay for school.

Since 2010, much of Mike and Nancy's previous retirement savings has been recovered due to stock market gains and their home’s valuation is back above pre-recession levels. However, they had almost no economic cushion and very little additional contribution to their retirement savings for nearly eight years. Now in their mid-sixties, both adults are eager to retire but still a bit uncertain about their economic stability if they remain healthy for another 20 years.

This couple happens to own a modest single-family home of about 2.000 square feet in an improving neighborhood that is near several large employers and walkable to a local retail district. Nancy has arthritis in her knees and has been pressing Mike to convert the main floor den into a master bedroom so that she no longer has to go up and down the stairs every night. However, this home improvement project will increase their monthly mortgage payment at a time when they are looking to cut down on their expenses and transition to retirement. Once a master suite is completed on the main floor, there will be nearly 800 square feet of space upstairs that goes largely unused.

Mike has been thinking about how easy it would be rent out the upstairs of the home. He could wall off the stairs and the front door so that a renter had their own entryway and, as long as they had contractors coming in to renovate the den to create the master bedroom, they could also install a kitchen upstairs and create a very nice two-bedroom apartment. Mike even went so far as to have his contractor put together an estimate for the upstairs conversion. It turns out, he could create a very nice second story apartment for about $60,000. The main floor master suite is likely to cost about $25,000, so the two projects combined would add about $85,000 to their total mortgage at a cost of roughly $425 in additional monthly payments. The average 2-bed, 1 bath apartment in the area rents for $972 per month. So, not only would creating a new rental within their home provide an opportunity for Mike and Nancy to age in place, it also creates a very affordable unit for a young couple or single adult who just might be a helpful neighbor to have if Mike and Nancy choose to travel in the winter and need someone to feed the cat or take in the mail. The best part is that the rent would fully pay for the ground floor master suite renovations and provide additional income as they enter retirement.

The problem is that the local zoning ordinance does not allow Mike and Nancy to add the apartment. Only single-family homes are permitted in their neighborhood, and nearly every other neighborhood in town. Despite the fact that they have plenty of extra livable space in their home that no one will be using any time soon, they do not have the ability to make it available.

Who wants that?!?!

It's not uncommon that people will be surprised to hear that some families would be willing to convert a portion of their home into a secondary dwelling unit. Very often they will say they can't imagine having someone else living upstairs (or downstairs). The good news is that we don't need very many households who want to do something like this. In fact, if just 3% of the total number of homeowners chose to add an apartment within their home, we could easily solve for the housing shortage in Ottawa County.

In 2017, Ottawa County had just over 106,000 homes with an owner-occupancy rate of more than 79%. Our 2018 Housing Needs Assessment shows demand for roughly 2,600 additional rental units priced below $1,250 per month.

We have been able to encourage the planning and development of nearly 1,800 additional apartments in new multi-unit buildings, but new construction is much more expensive than a renovation of an existing structure. In fact, it can cost anywhere from 2x to 5x as much to build a brand new apartment in a multi-unit building compared to allowing a homeowner to convert a portion of their existing home.

We have been able to encourage the planning and development of nearly 1,800 additional apartments in new multi-unit buildings, but new construction is much more expensive than a renovation of an existing structure. In fact, it can cost anywhere from 2x to 5x as much to build a brand new apartment in a multi-unit building compared to allowing a homeowner to convert a portion of their existing home.

The Role of Local Zoning

Following a 1926 Supreme Court hearing, zoning laws were ruled to be a constitutional power of local governments to regulate the use of land in order to promote and preserve public health, safety and welfare. However, it wasn't until the Post War building boom that zoning became a much more ubiquitous tool that was embraced by local communities. In the first few decades, zoning was largely used as a mechanism to prevent heavy polluting industry from locating within a largely residential neighborhood. By 1955, however, zoning was being used to segregate neighborhoods on the basis of building type - single family belongs here, two-family belongs over there, and multi-family belongs on the other side of the tracks.

Today most zoning codes are drastically limiting the ability of the private market to respond to the housing challenges of our time in an incremental and organic manner. In our current economic system of housing construction, we take for granted the idea that most housing is built and financed by large companies with the funds to construct dozens or hundreds of new housing units at a time. This system creates a fundamental risk/reward calculation that drives prices up.

We forget that there are tens of thousands of individual property owners with both the land and the financial resources available to add one or two additional housing options on their own property and at far less expense per unit than a large developer can achieve - if only the neighborhood and the local unit of government would allow them to do it.